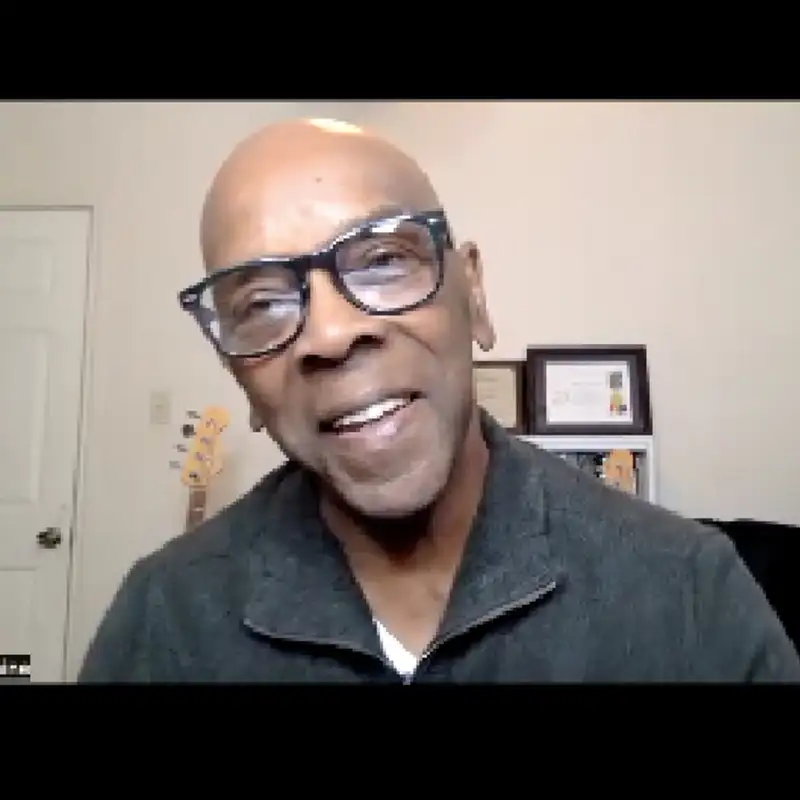

Rev. Jimi Calhoun on Transformation (Protect & Serve)

This unproofed / unedited transcript was generated by Otter.ai.

We will post a corrected version, asap. Thanks!

####################################

Chris Searles 0:01

Welcome to the all Creation Podcast. I'm Chris Searles, executive editor and co founder of all creation.org. And I'm also the editor of this issue envisioning transformation with my friend, Reverend Lewis Tillman. And in this episode, we get to talk with another of my favorite mentors. Reverend Jimmy Calhoun. Jimmy Calhoun is a man with a lifetime of leadership in human integration, celebration, and reconciliation. And before I read this intro, let me tell you, it's going to take a couple of minutes here. We all are people worthy of a four minute intro, but Jimmy's is a little more exciting and interesting than, than most of us. So here we go. Jimmy is today an author and ethicist who has been pastoring for nearly 40 years in various denominations and capacities. And since the 1960s, he has been an historically important musician and racial integrator. Jimmy is completing his fifth book and ministering weekly now to the disabled, and through his interdenominational church bridging austin.org. There is so much more I can say about Jimmy. He's appeared on all the major TV networks as a storyteller, for instance. And when I look at the contributions to culture and human well being that Jimmy's lifetime of work is, I see a man who has been transformative since he was a kid in California in ways that are inclusive and beneficial to everyone. And that is the institutional transformation we are exploring, seeking and envisioning in this conversation. And in this collection. Jimmy was raised in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1950s and 60s. He grew up there during what I consider to be the most positive transformation period in American cultural history, literally co powering the epicenter of the 60s West Coast hippie youth movement to integrate all people through our affinities. Our shared loves, and music was a huge part of that. Jimmy was playing bass with soul and r&b stars like Lou Rawls and Wilson Pickett before he could drive. By the time he retired for music in the early 1980s. He had helped define bass playing in three genres of 20th century American music, West Coast, funk, New Orleans, funk, and funk rock.

Note the repetition of the word funk.

Jimmy did this by playing bass on Legendary recordings with Parliament Funkadelic, Dr. John Sly Stone and three albums with his own band creation, and many many more albums playing on dozens of uncredited recordings, such as the Rolling Stones Exile on Main Street. So all of that was a big deal. However, in 1983, Jimmy left the music industry and became a Christian pastor, dedicating his life to people and peace. Since the 90s, he and his wife julaine have lived all over, helping 1000s of people in millions of ways. Currently, one of their ministries focuses on worship inclusion for people with disabilities. Worship for people with disabilities, it is breathtaking. Reverend Calhoun has four books on reconciliation. One readers quote about Jimmy's fourth book, turns out that being love is funk Knology. So, it is a great honor to have you here, Jimmy. I'm a fan on many levels. And to the audience. I see Reverend Calhoun, as a man who is all in on the things he cares about a person who lives in his integrity, in large part by helping others. Jimmy,

sir, welcome to the podcast.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 3:44

Thank you for having me,

Chris. That was overwhelming to hear, to hear your, your characterization of the things I've been involved with over the years, but I'm appreciative nonetheless.

Chris Searles 4:00

Yeah, it's a it's a mouthful. And it's, it's also really exciting to talk to you. Okay, so our topic is transformation. And I wanted to ask you how you have experienced transformation, you have this unique place in history. And also why transformation and an envisioning transformation is difficult for people to see why it's difficult to envision transformation. And then inside of that as well, if you can talk about the kinds of transformations that religious institutions need to seek, you know, what, what criteria how do we, where is the compass, the North Star for, for transformation today? Well, I

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 4:38

think the beginning is probably where I should begin where you began, and that's from a historical perspective. And as noted earlier, I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area at I came of age, you know, like a young adulthood justice. The hippie movement was what was ascending to be a cultural phenomenon the United States. And it's hard to imagine how how much of an impact it had. Because in retrospect, because it seeped into the culture in our culture is what it is today. Partially, because actually in a large part because of what was happening then. So I can just give you a couple of basic things that I observed as a young young man watching all of these things converge, you know, at that time, it was only London, New York and San Francisco. And actually, San Francisco was the leader world globally. And, to put it, to put it briefly, I would say that transcendence actually preceded transformation. And what I mean by that, if there was something that people saw going on, that was larger than what the change that needed to follow, there were some questions that were asked. And what happened, how the society was transformed, was actually in response to the question. So in that sense, it was, it might sound a little bit cliche is but you know,

who are we?

Why are we here? And why are we doing this? And that's in relationship to life. And in the Beatles, who were the cultural leaders of the spokesperson, for my generation, you know, they went all over the place looking for they went to India and they had gurus and out in San Francisco, we were experimenting with different other ways of trying to find ways to, in one word, enlightenment, but when, you know, enlightenment can sound kind of cliche itself. But if you break it down and look at the root word, it just means that don't put a light on something like a spotlight, you're in a dark room, you want to see what's in a put a light on, you know, you're in a dark space, culturally, what do you want to do put a light on it, so you want to be enlightened? So in that sense, there's something that we we've lost our sense of with mystery and wonder. We don't we're not looking beyond the everyday mundane accumulation of goods and materials stuff, and that we're not living in two places at once. We're not, we're not living in the now looking to the future. So from my perspective, transformation needs a little bit of both

Chris Searles 7:53

needs, both in the sense of living in the now and look into the future. Correct it?

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 7:58

Yeah. Not only what is is what could be.

Chris Searles 8:02

So then, how do we you know, right now, we're, it's December 2 2022. And we're still in the midst of a very polarized American culture, for instance, that's on most people's minds that I talked to you right now. How does society kind of come together around this idea of saying, Who are we? Because I think right now, they're, you know, they're very different perspectives on what that means. But we haven't found a common understanding just in the United States.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 8:30

Yeah, certainly. And I agree wholeheartedly we, Chris, and yeah. Our political system is adversarial. I mean, by definition, we have two parties. And so therefore, it's, it should be no surprise, that we're going to have disagreements. But disagreements should only be on the issues, not the essentials. And what I think you're saying by being polarized is we've crossed the line from disagreeing with people to being disagreeable with people. And we, and I've seen from a pastoral viewpoint, I've seen politics cause families to fragment when people don't speak to other people because of the lever they pulled on whatever particular election and from my view that ought not to be and that's that's mostly what my writing and my my life and my ministry is about is bridging those things that seem unbridgeable. You know, that we think this is just too that's a bridge too far. I can't cry. I mean, you voted for my enemy. How can I speak to you anymore? I mean, how can you be this and you love them before you found out? You're there voted for it, it took a few sentences for you to get to the point where you realize that they voted for somebody you didn't like. So that same person you love five minutes ago, you can still love, you can strongly disagree with them. And you can disagree with their choice. But there's no reason you got to tell them, you know, the proverbial baby out with the bathwater. If I

Chris Searles 10:24

may ask this of you, because you're such an experienced caregiver, I think I was thinking about this, you know, from the perspective of engaging people, you know, on a daily basis, every every interaction, if we were to just take one step back for the audience that's listening. You know, you and I met because of an event we did, entitled, called to care that's also featured in this issue. And, and the idea there was, you know, what about what if care were identity? You know, if we put that first and our identity, we default to care, in every situation before judgment, so on and so forth. And why can't we, you know, and I was thinking about this in the context of envisioning transformation. And I was thinking, okay, so skipping ahead a little bit, and some of the conversations you and I have had, in a way, transformation of institutions is about making them more caring for every single individual. And that's what they're doing wrong in a way is they're, they're fundamentally rooted in a white patriarchy of, you know, Western European slash American industrialization and digitization effectively, you know, and, and the institutions were built that way for a lot of reasons, and did a lot of terrible things, and a lot of good things. And now, here we are, and, and when you think about a world that's based in carrying, trying to engage with every individual, you know, you as you engaging with me, and then with the neighbor across the street and the mailman, or whatever, like, we should make a mental switch that we should expect there to be differences, you know, instead of this thing of fearing, conflict and fearing awkwardness. And so we should actually go to the differences, we should know that, you know, just as you know, when you go to the disabled, for instance, there's no way that you're going to be in the same place. Literally, you're not going to that person expecting them to affirm you through your political beliefs or whatever, right? And so we're in this funny kind of, I think, wrong, you know, rootedness about that. And I'm curious if conversation was sort of different back in the 60s and 70s interracially enter economically intergenerationally, maybe in that way that people were less concerned about, oh, my God, this could be uncomfortable and more going, hey, you know, what do we what's different about us? And what do we both love? You know, I've heard you talk about this idea of connecting through our affinities.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 13:01

Well, culturally, things definitely changed. But it wasn't a smooth,

linear happening.

I mean, there was there was a lot of tumult and turmoil and protesting and people not wanting to give an inch, and then they realize the inch was on the other side of them, so they better retreat. I mean, there's a I guess there's two things I would say to that. And one about care. I think I need to preface this with hearing me speak. I'm not utopian. I'm not a naive, utopian.

Chris Searles 13:42

One of my favorite quotes by you is, it's much better to have an honest discussion than a polite discussion.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 13:50

But I am altruistic. And I do believe better is possible. But I think it's also hard to achieve. And sometimes we have to step out there and we don't know what the end is going to be. And we can't do the Stephen Covey start with the end in mind because the end isn't discernible right now. We know what it would like to be we would like it to be a more loving, caring society. But it's hard. And we're individuals with different frames and different frames of reference and that Chris brought up the disabled community. We started a church and primarily to be a church, for people living with a disability. Now there's a distinction between a church with people living with a disability. We started it because we wanted them to be included in the liturgy. And every activity that was going on in the church, rather than a church, we function as able bodied and they get to watch us do our thing. By sitting in another room by being piped in, or sitting in the back, or sitting in the front, whichever. So we wanted to blend this melding this amalgam of people who are able bodied and people who are challenged physically or intellectually challenged, there was a problem, in that there's so much variety within the disabled community. That and just like there is in the able bodied community, it's intricate, and it takes it takes

a lot of

tender loving care to blend them together, I'll just give you one story. We have a person reading part of the biblical passage who had an intellectual disability. And so they would read four or five sentences and have to start over, then every five or six more sentences, and have to start over again. Well, the people with a physical disability in the wheelchair lost patience with the other person with a disability different than theirs. And they came to me and said, You got to stop that person from reading because it was taking too much time. I'm not enjoying the service if you let them read. And I thought, Wow, what an illustration for how challenging it is in the broader culture, to have people be patient with the other while they're pursuing what it is they're trying to input and contribute to the overall conversation. We're not a very patient society. So when you brought up disability, I thought about that is not only a metaphor, but an illustration about the challenge that we face when we try to bring people together who come from various walks of life, racially, physically, socio economically, geographically that I mean, there's just so many challenges that we have to overcome before real transformation is even them before we even start the process.

Chris Searles 17:07

Yeah, yes. And

in that line, I want to ask you about feelings. Because to me, the thing I hear there is that, you know, most President my life, or rather, my sort of revelations right now is just recognizing that, you know, you're talking about one person getting impatient with another person. Alright, there's sort of one basic dynamic there. And what's interesting to me to go one lot, one more time back to your, you know, 60s 70s 80s 90s kind of life. In the 60s, things began to propel themselves. And you know, there was an idealistic vision in there to some degree, there was youth energy in there to some degree. But I also think there were two important components that we haven't focused on as an American culture, at least one of them, you know, which is like our potential, what can we do? How good can we make the future? And the other one, I think, is, it literally felt good, probably to be, you know, you're talking about there's this again, but going back to the 60s, in particular, the civil rights movement, there's an enormous conflict, real conflict, and real violence and the things that people are really afraid of happening today, and so on and so forth, at at a greater scale. And, and so one of the ways that was, or one of the things that was balancing living in that was the music and the culture and the, you know, FlowerPower this tie dye the, the explosion of like, celebration of this positive energy, and, you know, like, you've told me, you grew up with sly. And that that footage of Sly, and the Family Stone in the movie and Harlem, that was the logo. And I think it's 71 or so, you know, right before so I kind of had a downfall there was earlier earlier 69 Maybe they are the freshest band in the world, maybe ever at that moment. And there's just such an energy there. That's explosive and exciting. And so that's, you know, emotionally that feels so good. Right. And one last thing is we're talking in a different interview, I was talking with a woman named Marge Barlow about her project and feminism, and her ongoing effort to sort of help women see their potential. And it's like these things. They're, you know, better than durable, they're upward cycling, because it is about tapping into our potential. So, in a way, no matter how bad things have gotten for hippies, you know, in the real world since the 70s, you know, financial baby boomer ism, and all this kind of stuff that is reality in this current, you know, economic context, those things, those values of being individuals and, you know, coming together, those things get stronger, I think, as we get closer to being, you know, true to ourselves, and that's a feeling that It feels good in your body to be that person and to be with other people like that. That's my impression. I'm curious if you can relate to any of that having been there, you know, 60 years ago, 50 years ago.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 20:13

You remember, many years ago, okay, just to the hippie movement. And I grew up in a religious family, my parents were in ministry, both my grandparents, and my brother and I have an older brother who's named Bill and he was much more musically talented than me. His vans used to be the big cheese. We mentioned slide when my brother's bands were higher, as far as Bay Area stuff. But he left to go into he joined the Black Panther Party as soon as it formed. And he became, you can see, there's, there's a lot there's movies and books out about bill right now. And that meant he went to Oakland side. And I went to the San Francisco side with a FlowerPower, I became a hippie and worked and did everything. And I protested the war and got my head beat in. And he told me recently that, you know, he used to take the Black Panther newspaper and have a gun and go out and vote in New York to have them printed. And, you know, our lives were completely different. In my first book, I told the story about a Black Panther came up to me and said, you know, you and sly and Jimmy and Buddy and Taj Mahal, you guys are going to have to pick aside when when the when the revolution comes, right? You don't want to be left behind? Well, you know, there was this anticipation of a revolution and armed upheaval, and the world is going to be turned upside down. Well, that guy who said it, I didn't put it in the book was my brother. I didn't want to the movies came out. So he's been outed. So now I can do that. But, but the point in this was, my brother saw one way to make a better world. Geographically, he went 15 miles on the other side, I saw a different way to make a better world and I went up and we had what on the surface would have appeared to be two diametrically opposed method, the methodology seemed to be in conflict. And in the last couple of years, he sat on my couch, and he says, you know, Jimmy, you know, we both got involved, and we did all this stuff. And here we are, you know, in late in life, and it turns out, we were always chasing the same thing. And that same thing was always peace, for a greater number of people so that they can enjoy their life. And they can maximize their potential. And they were free to be who they wanted to be, and who they were created to be. And that that really, ultimately, is the the challenge. How do we make that accessible, and not to be John Locke or anything for the greatest amount of people it's not, it's not a social contract. What it is, it's a, it's a biblical way of looking at the world, that if there's this God that I'm ordained to serve, then that person has an interest and vested interest or vested interest, and every single human being that's living on the planet right now. And my job, my challenge, and I've I've willingly accepted it is to see how I can be a benefit. How I can help others see the need to be of benefit to the next person to come in contact with, it might be an ATV, the market here, it might be, you know, getting on a bus to train the plane, wherever it is, that next person you see has value and worth.

Irrespective of the shape you find them in. How are you going to see them

and be a part of moving them along with the hope that you know, they talk about pay it forward? But you know, that only works if it's in a circle? You know, everybody's paying for it, but while you're doing it, somebody's behind you doing it for you? And that's that's that's the thing. That's the bridge

Chris Searles 24:31

Yeah, I think and this might be a good way to tie over to the question on creation care, too. You know, I, I do question the sort of actualization I'll say, since that popped out of my mouth of behavior, you know, that in the world of religion, every individual is not looked at, as, you know, this incredibly miraculous ball of potential that we don't go to each individual this excitement instead, we're trying to just figure out how not to harm each other in a way still, you know, 60 years after the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement becoming mainstream,

in America maybe. And

from a large historical arc, it's it's certainly understandable, there's, you know, a big old planet out there, and a lot of human culture in America is in the leading position to some degree. And San Francisco really was the leading place, I think, historically, so far, in demonstrating kind of best behavior. But creation care to me, for a religious person for a Christian person is at, you know, maybe a logical level, at the very least, about that same approach. And it's it isn't, you know, Genesis one, this idea of being a care provider. So do you for the other life on our planet? So do you have, you know, a way of understanding creation care that relates to the way you understand human care?

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 25:58

I think they're inextricably linked. One doesn't happen without the other. And they're intertwined in length, and they're one in the same sentence. And getting to Genesis one, we're talking about the have fuel rule over Have dominion or whatever, whichever way you want to define that word. That was only a statement, that was a one time statement. But if you look at Genesis two, this repeated with an added

mandate, God days

added list of instructions. And when I grew up all the police cars, even the ones who were coming to knock our heads when we were protesting the war, it said to protect and serve. And, you know, that was initially that was what the police, their job, their role or job description was, was to protect and serve the public. Their job was to provide civic good, you know, not to go searching out for bad guys, if if there was an offender, then you arrested them. It wasn't a proactive job that happened in another country at another time when you went around deciding who was the criminal already, and then going and confronting them. That was that's for Germans, and that was, we know how that turned out,

Chris Searles 27:28

protect and serve as opposed to seek and destroy,

correct?

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 27:32

Yeah, that's a good way of saying. And ironically, in the Bible in Genesis two,

that was our mandate to the earth, we're supposed to guard it, and not rule over it in the sense of being a master. But to serve it, in the way of being Jesus who came to be a servant to many.

At a time. If we believe the biblical story about Jesus, he could have been the baddest dude that ever the baddest of the bad because he had all power in the world at his disposal, and chose to use none of it. So the idea that if I give you power over something that you have to immediately use, it runs contradictory to the Bible story, I mean, that you can't find it there. So I mean, that's where you're, you're extracting principles for your own personal use, rather than submitting to the story, as given. And so in my view, creation story is one of we're a part of

this bigger story. And our role is to protect and serve.

We don't want to become the seek and destroy.

Chris Searles 29:06

Can you talk? Can you talk also about, you've used this phrase biblical ecology,

and what that means,

you know, in this context, is that about creation care? Or is that about human relationships? How do you mean biblical ecology

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 29:21

was about creation care, that that's the thing, and that is that the idea of protecting and serving, but I mean, we can carry that over to each every, every human being, we do have a role to protect and serve each other.

Those are two simple words,

but you try it. Try being a servant to someone without reciprocity, you know, without just trying to love them and want what's best for them and do what's best for them. And if they don't respond the way you want, we quit. That's human nature. You know? We're in a market economy, even in terms of material goods, but the way we see the world, everything is contractual, it's an exchange we want. And then we, we decide whether it was a fair exchange. And once we feel like it's not a fair exchange, we feel we have the right to withdraw. But in a covenantal relationship, and with a responsibility, you have to keep going, no matter what the other person does, you have to push ahead, if they don't carry their load that's on them, you do your part, regardless of the outcome, or whatever it is, you know, you know, you do what you're supposed to do. So, you know, in that sense, that is creation care, you know, I have a responsibility to be conscious of how my behavior and everything impacts and experts and not because it's a rule, but because I care about the next person, I want them, you know, I want them to be able to drive down the street without my car being blocking their street.

Chris Searles 31:12

I want to sort of follow into that a little deeper. So it's hard to pay it forward. It's hard to do things for people. And what I perceived to be a time where we're particularly kind of out of balance from trauma and neglect, and depravity and abuse, institutionally And historically, and, you know, it's, it's certainly never been perfect, right. But the human society has never been perfect. But when you try to turn the other cheek, as it were, you know, sometimes the people that you're dealing with, for instance, in this congregation of disabled people relative to, you know, an easier the mega church or something. Like, they keep slapping for a while they have a lot of needs, you know, and you really have to serve, like you said, you really have to be strong to serve. I'm just sort of curious how you see that, you know, that that long process of change the you go up, three steps forward, and then four steps back, and then four steps forward, and two steps back, and you know, the the emotional aspects of healing and things. How do you kind of do that in your work and, and then also on the larger idea of reparations, and, you know, race history and things like that, if you can talk about that?

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 32:29

Well, that's. Yeah, I mean, it's talking about human rights, where we were just where we left off was talking about human responsibilities. The two are words of the I would choose responsibilities. And then there's something there's something that I put in my third book about to shuba is this concept of restorative

justice. And

we don't like to think in terms of restorative justice, we like to think in terms of punitive justice. And what I mean by that is if somebody took my new Corvette, and they drove it to Florida, and the police found them in Florida, and they said, Well, you gotta get Jimmy's new Corvette back. He goes, I don't want to, you know, take me to jail for five years. You know, in our mindset, we might be happy that you got what's coming to him. Turkeys in jail for five years, when you're still without a car. The car, still in Florida, he's not giving it he's not telling the where it is. And when he gets out of jail, everything is called even then he goes back and he has a car with zero miles on

it. But

Restorative Justice says, Okay, you're not going to be freed of anything until you take that car back and make that person whole. That's quite different making the other person home. And so then we have this idea of not reparations, but making

the earth home, people within the earth home.

Let's, for lack of a better term, let's use recreation. We should be involved in the process of recreation, there was a creation from a religious standpoint that God did, but he's given us the responsibility and the job to be involved in recreation.

I hope that makes sense.

Chris Searles 34:45

You mean, sort of

advancing again, in a way like you know, an Eric one air ends and other air begins.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 34:54

That's certainly part of it, but not necessarily even from the creative, like you and I think because we're both music So we think in terms of, well, let's create a part. There, there's a whole layer that something's not happening. Let's make up something, you know, let's invent let's create. No, I'm talking about more than, like the Bible says, One creation happened. There was a conversation said, This is good. Well, if we look around, and we're not saying that it's good, then we've got to make it good. So that's, in a way restoring, but it's recreating because it was once created, to be good. So now if it's going downhill a little bit, then we need to recreate it so that it returns to its normalcy. So it returns to a place where that sentence could be said, once again, and that's good. So regression in that context,

Chris Searles 35:51

well, let me try to thread together another piece of this that we've talked about, you know, the idea of making every one hole. And I feel like a moment ago, you were talking about how you may I may have this totally wrong, but how, you know, it's almost impossible sort of, for every human being to have a high quality of dignity and life. I know I have that wrong. That's a bad summary of what you were saying. But, but what I was trying to get to is, I think that is how we're thinking right now is that there's a hopelessness in the air, about humanity. And when you say things, like, make everyone whole, that rings the bell of this kinship idea that we've talked about, and that came out in the most recent creation, where we change our worldview, you know, we begin to look at every individual as important, and we begin to look at society as a vessel for nurturing. So the this, you know, academic definition of kinship worldview, is that everyone is an important individual in a nurturing community. And, you know, how do you change the whole world? Well, I mean, again, to me, it's like it's this feeling, you start to feel better, because you're around people who care about you, and you

have a good time with. Things start to move in a better direction.

I don't know. These are simplifications I'm offering.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 37:09

Yeah, that's, that's really good. And I will say this to that. And in the book, my forthcoming book, I do talk about kinship, and kin folk primarily, because when, in the early days, it was a truly good band and Oakland call the kinfolk, man, and they were they were just, I was only 14 or so but then they were the bomb. And

Chris Searles 37:34

it was just also an interracial band. No, they were

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 37:37

the kinfolk were from Oakland. And and I guess you can say that Oakland kind of means they were African American uncle was always

Chris Searles 37:44

primarily African American. Oh, yeah,

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 37:46

very much. And so the kinfolk, there's a good parallel there, because you can call a kinfolk or an all black band would be careful. Because we naturally assume kin or quote, like us, not be the best and the most accurate use of the term or the idea of being in kin, or being in kinship, because the, the word can comes from the Old English word, which might be pronounced the same way. But it's spelled C y n, n can sin, you know, and that's that old English word by definition met

race.

It also meant family. And it also meant kind. So then that kept that question comes up. What do I mean, when I say my own kind? Do I mean, all handsome bass players or handsome musicians? Or do I mean, everybody who's from California and is vegetarian? Or do I mean everybody who likes sports cars? Or, you know, what are my kind? And that's a question we, we just seem to take for granted. And the what we turn to most often in America is skin color. But what that will do is get a Stanford grad or a Harvard grad, a white Harvard grad on a desert island with a white ex convicts who only went to the eighth grade, and their skin color is not going to be much of a bonding agent in that circumstance, because they're going to have absolutely nothing in common. So, you know, we really need to be careful and we just assume we knew know who are our kind are and maybe it's wise to have an expansionist view and say, everyone is our kind. They're just different kinds. And that's why that word can or sin, when it's broken down in this definition. It already had three different kinds of that you wouldn't think Were part of the same word, but they were, that's what the word meant. And so variety and diversity, you can see diversity is already built in the universe, it should not take a degree from Harvard to figure out that diversity is natural, and it's a good thing

Chris Searles 40:23

do you have it, you want to take a shot at talking about why we fight against it? As I threw in there, diversity is reality. You know, the thing I like to say, as the environmental advocate is, we emerged into a biodiversity planet. And that's even in the creation story, you can, you can look at that. And all of the different sacred texts as well, that was a life rich planet when we got here. And we depend on that as the life support system. And it's the same as the, you know, this metaphor of the human ecosystem, where all the relationships you have that sustain, you know, we depend on diversity, and then your own body and your own life, you change your Kaleidoscope your whole life. And so diversity is reality. And yet, as you said, you know, we fight against it. So

do you want to take a swing at

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 41:09

a really large bat? You know, that's a

Chris Searles 41:13

big thought about it. Yeah. Right.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 41:15

That's, that's, that's, that's, uh, you know, I could give you some answers from reading or from my religious training, you know, but they wouldn't be very satisfying, because they would only cover a small segment of the population. And, you know, it's why cognitive ability is so important that we're able to override some of our natural inclinations, because we can think, and we can say, Oh, well, you know, running five miles a day hurts, and my body doesn't want to do it. But then when I do it, when I went to the doctor, the doctor said, Well, you're in better health than you were a year ago. And then I can go home and say, Well, I think I want to be in good health. So I'll keep running body, you have to do this, and I'm gonna make you do it, I'm gonna make you get out and walk out of that door, and you're gonna get put on running shoes run down the street. Okay. So I had to override that natural inclination to say, no, that's too tough, I ain't doing that man. You know, I don't want to do that. And the being aware and appreciative of the diversity that exists, is hard work. It always doesn't come natural, I think we're basically lazy. We want everything to come to us, we have the sense of entitlement. If it's something that is that doesn't please me or come naturally, that I have no responsibility to, to try to twist or change my way of thinking. So that I either appreciate it or get involved in it, where we're to whatever level you want to be, we don't we just don't think we have a responsibility to do that. And so if there's somebody if there's a whole community that lives across, down, and they they have this cultural way of looking at the world, and they're doing this, they just came from Bangladesh, and there's 7000 of them. And as long as they stay there, then I don't have any responsibility towards them. But the Wiser course of action is to get in your car and go over and you'll find some great food, great people. And you'll you'll find some language and they use words to describe things that you that you never thought I never thought I saw that. That words better than the English word. That's more descriptive, that works better, that fits better, all these exciting things that come out of diversity, and some attributed to fear, but I would, I don't think anybody's afraid. I think they're lazy, more like the running out of I mean, my life's going swimmingly right now why should I change? Everything is good for me. I have a good job a good car to this and why do I need to be thinking about what's going on and Belize Central America down? And, you know, there's no recent way to think of those things. So I would say the biggest adversary to the appreciation of diversity is a partially fear, but it's laziness. We just years ago, they used to say there were involved in culture wars there between the right and the left and who's gonna win who's gonna prevail. But, you know, I, we're, we're pretty much in the comfort wars, you know, we're, we're in battles about see how comfortable we can be and anything that's construed as making our lives more comfortable is good. And anything that requires getting out of that box is bad. And we will just leave it right there. We just assumed it didn't exist. So that's probably all I can add to that,

Chris Searles 44:56

Tie this

to one great point, I think that everyone needs to hear. Like when you're out there doing this service work, and I can't think of too many things that are more service oriented than a congregation, for disabled people, that is about them, not about just inclusion, but about building the worship for them. That is service when you're doing that, that feels good, right? I mean, it's not easy every day. And there's a lot of complications around pulling that off. But it gives you

a lot.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 45:31

It gives me a lot and also tells me a lot about myself. Yeah, it's back to that duality, you know, there are things I want to do, and there are things I should be doing. And they don't always come together naturally.

There's one story.

About five years ago, there was this, this guy, and this one place, and he drew, and he walked around with a bag. And it seemed like every time I got to the door, he was there. And he always

wanted to hug me. And I didn't want

oh, you know, and I got every week I went to this one place. And it seemed like, weekly, he was like, he knew I was coming somehow there was this, he got this late and for you. He was waiting, were laying for it on until they hit the door. There he was.

And, you know,

I felt bad because there was just fragrance of urine, you know, he would just go whenever he can. And you know, and well COVID hit. So I didn't see him for two years.

We're just starting to

go be allowed to go back in and have content. And three weeks ago, three to four weeks ago, Robert and I went.

And there he was. And

he looked at me and I looked at him. And this big smile came across his face. But in the interim, whatever of medical problems he had had been fixed. And now they cleaned him up. And he's sitting there now He almost looks quote, normal. And he had this big smile. Because he's known me for the last nine to 10 years. But he never knew what I was thinking of him. He never knew that, even though it appeared

that I was accepting of him.

It was challenging for me every time I saw him. And I had these thoughts that I didn't think should be there.

But the moral of the story is I overrode the thoughts. And I kept coming back.

And I kept coming back and time. Over time, what was hard, difficult and abnormal, became normal. Yeah,

Chris Searles 48:06

and things get better in that long

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 48:15

I can communicate with as a result,

Chris Searles 48:20

I just I'll ask one more question on a personal level, and then ask the final question on a podcast level. You know, as an advocate, the way I look at progress now is like switchbacks on a mountain, or 3d printing in a way, you know, and you go back and forth, and back and forth, and back and forth, and back and forth. And you are making progress. But sometimes the trail goes down. Sometimes the trail goes up the the two years, I'm not seeing that guy was part of a 10 year journey. Yeah, now things are in a better place. And if you had looked 10 years ago to what can we do? You know, I mean, just it's, it's hard to predict how to get things right. But it is that long, sticking together thing.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 49:03

Yeah, I think crucially, I think the word that you use your sin was is vital. I mean, predict, prognosticate. If I do this, what will happen, not only what's going to happen for me or to me, we, we think in those terms, you know, it's back to that contractual way we see life. You know, it's all a matter of give and take. And sometimes the things you and I are involved with, it's a matter of give and give. And that's, that's, that's fatiguing and challenging. But I will say, I'll give you a racial story. We lived in Florida before we moved to Texas. And so probably 1516 years ago. We lived in Boca Raton, we walked into this ice cream shop and my wife is white and I look how I look and we walked into this ice cream store. And the propriety goes turned around. And he was shocked. He goes, What are you looking at that? It was it was one of those statements in disgust, that rather than thinking he verbalize it audibly, and we can hear it. And my wife loved this particular type of ice cream, because she's lactose intolerant, and was the only place we could get this Carmelites stuff that they've made for people on that type of diet, this Atkins diet that wasn't made from dairy, they've made it from whey and is, so we had to, we had no choice but to go back and my wife was going to enjoy ice cream, I had to go with her and I had to see this guy who didn't think we should be married. So you know, we would go for however long, once a week, we would go to this, this ice cream store. And my birthday was three weeks ago. And I went to the post, and I got a birthday card, from the proprietor of that store. No way over time, just because we came so many times, we became friends. Not only did we become friends, we became close friends. To the point I was in his house, when his wife died, I was at the service. And he sends me cards, Christmas cards, and he signs them, I love you. And the thing about that is I just kept coming back even though I was uncomfortable. I invested the time I invested the energy. And the person was as we use the word transformed his way of looking at life at looking at me at looking at the things I was doing changed. But it didn't happen as a result of me confronting him and saying, Hey, bucko, we're both human. What's wrong? What's your problem? Let me tell you what you need to be doing what you need to be thinking. And I have seven books, I can show you that say I'm right, and you're wrong. So let's get to it. That didn't happen that way. It happened through long term engagement, patience, and uncomfortability on my part, as Western people were result oriented, rather than process oriented, and sometimes the ethics involved matter a little, as long as we can hold up the result and point to it, then that's considered to be good, and we're celebrating. But that's to the detriment or overlooking the process of how we got there. And to have transformation that's going to be lasting, or meaningful. Sometimes that requires us to be process oriented, and do the snail trail and just bit by bit, and just keep plodding along and getting it done. And the results will come in due time, having the patience to see them come is

is the challenge. And

you have to remind yourself over I'm doing this because I'm doing this because I'm doing this because if I can change one life, one heart in Lansing, Michigan, and one in San Diego, California, then all of those hours over the computer are worth it. And I think it's that way with most things that are meaningful and worth doing. So this saying that we're involved in trying to make a world a better place. I had made this metaphor, the Great Wall of China, it wasn't built brick by brick. It was built ideological Brick by Brick over a long period of time. And even when it was finished, it didn't achieve the desired results. But to tear it down, we have to do the reverse ideological Brick by Brick dismantling, as in the case of this guy's view of interracial marriage, it had to be this it had to be dismantle by my loving him to the point where I buy his ice cream and not give him stinkface

Chris Searles 54:35

Wow, yeah.

I don't I don't think there's a stronger message than that. Thank you, Jimmy. That's yeah, that's that's a whole lot to live with and live on. And this has been Reverend Jim Calhoun. Thank you for being here. Jimmy.

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 54:54

Thank you, my friend.

Chris Searles 54:58

And I know

our our podcast is over. If I have another written down another quote from you, that ties to what you just said, all meaningful change has to come at levels where commerce is not happening. Yeah. So you're talking about relationships and identity and culture and you know, I we live together just

Rev. Jimi Calhoun 55:18

Fundamentally, that's what that's what it's all about to me. Yeah, yeah. That's my life!